Spotlight on: Minimum wage – A dozen questions about the National Minimum Wage

- A national minimum wage was mooted, investigated and ultimately recommended by a panel of experts appointed by Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa in October 2016.

- The panel proposed that a national minimum wage be set at R20 an hour, the equivalent of R3 500 per month for full-time employees.

- A sober examination of the proposed high NMW reveals unacceptably high levels of risk and a very high chance of exacerbating poverty, inequality and unemployment, while also slowing economic growth.

- Should a country in SA’s position with one of the highest unemployment levels in the world – close to 40% of the workforce – play Russian Roulette with the livelihoods of tens or hundreds of thousands of people?

The Panel recommends that an NMW be set at R20ph/R3,500pm, and that it should be implemented in late 2017 after the relevant legislation has been passed.

The proposal is that, in time, the new NMW will govern the employment of all workers, replacing all sectoral determinations and any collective bargaining agreement that sets minimum wages below this figure. However, the Panel also proposes some exemptions and exceptions, especially for the initial period after implementation (see Question 6).

For the first two years after implementation, it is proposed that no sanctions be imposed on employers who do not comply with the minimum wage, and that the level itself not be adjusted until it is possible for the relevant Commission(see Question 2, below) to study its effects carefully. In practice, this means that the NMW will remain at R3,500pm until 2019/20, and that failure to comply with it will not be met with sanctions until that date (see Question 4).

One of the most critical features of any minimum wage regime is how its level is changed over time, with different approaches seeking to balance two distinct dangers. On the one hand, a system of automatic adjustment – where the level of the minimum wage changes automatically in response to inflation, growth, and productivity– risks creating inflationary feedback loops that can make monetary policy more difficult to implement. On the other hand, a system in which minimum wages are adjusted by regulatory fiat allows officials to adjust the rate of increase to the needs of the economy (e.g. by increasing it by less than inflation when unemployment increases). The danger with this approach, however, is that it risks politicisation of these decisions, and creates incentives for politicians to promise to raise wages irrespective of the damage that might be done to the rest of the economy.

In this proposal, NMW adjustment is driven by a commission composed of experts on the labour market and representatives of organised business and labour, which would consider various factors before making a proposal to government on any adjustments that might be needed, with that recommendation being implemented only after the commission has had an opportunity to consider any comments from government and make adjustments to is, if needed. This is similar to the system in the UK, and, in principle, allows government to adjust the NMW in response to the needs of the economy, employers, workers and the unemployed on the basis of high quality empirical research, submissions from interested parties, and the expertise and judgment of members of the commission. This has the virtues of avoiding the potential of wage indexation, which can lead to inflationary spiral, and of allowing adjustments to the NMW to reflect economic conditions. It does, however, create the risk that debates and decisions of the commission might be politicised so that wage adjustments reflect the political cycle more than the business cycle.

Although the NMW is intended to achieve a number of goals, the most important is to raise the incomes of the working poor. According to Panel figures, the average per capita income of the poorest 29 million South Africans who live in the poorest 40% of households is about R500 per month. And, while poverty in these households is largely because so few people work (on average, each has only 0.6 members in employment), even those who do work earn very little: the Panel estimates that wage earners in this group earn on average less than R1,500pm.

The Panel’s report includes a series of tables estimating how many people are employed at wages below various levels, both in aggregate and per industry. It should be noted that there are some serious methodological concerns with the way data on income is captured in SA, with some evidence that gross wages (especially among those in the formal sector) are often underestimated. This is because people report their incomes after deductions (for tax, pension and medical aid contribution, UIF and even garnishee orders), rather than the value of their wages before those deductions. This creates an upward bias in estimates of the number of people earning less than any given monthly wage.

These deficiencies notwithstanding, according to the figures used by the Panel: 4.6 million people (35% of all employed people) earn less than R2,000pm; 5.5 million (42%) earn less than R3,000; 6.2 million (47%) earn less than R3,500, and 6.7 million (51%) earn less than R4,000. While the precise figures differ for each cut off line, the industries in which the largest proportions of all workers earn low salaries are, domestic work (where 91% of employees reportedly earn less than R3,500pm), agriculture (85%), construction (55%), and trade (48%). At the other end of the; scale, it is only in utilities (24%) and mining (18%) that fewer than one in four workers earn less than R3,500pm.

The Panel acknowledges that an NMW cannot be expected to reduce poverty by reducing unemployment. It accepts the general proposition that there is a trade-off between wages and employment. Even so, it argues that by raising the statutory minimum wage, households in which there are employed people will be better off. This is contingent, however, on their remaining in employment, an issue to which we turn in (see Questions 8 and 9).

The Panel estimates that 6.2 million people – or 47% of all workers – currently earn less than R3,500pm, and that this is the number of potential beneficiaries. There are reasons to be sceptical, however.

The Panel has included people whose incomes will not rise

Although the estimates of how many people earn below certain income cut-offs appear to exclude 1.2 million “own account workers” (i.e. people who work for themselves) and nearly 800,000 “employers”, they do include part-time workers and employees in informal enterprises. The Panel does not estimate the number of people earning less than the proposed NMW and who are either part-time workers or in the informal sector, however, it acknowledges that an NMW may make little difference to many of them.

In the case of part-time workers, their monthly incomes may be below the potential minima, but their hourly wages may be above R20ph. Panel members have noted that they expect some employers will reduce the number of hours employees work in response to the raised hourly wage, so many workers may see no additional income (though they will have more time off). In the case of informal sector employees, the Panel acknowledges that an NMW will not be enforceable. This would imply that the estimates of people earning below R3,500ph, for example, is an inflated estimate of the number of potential beneficiaries of an NMW set at that level.

The impact of inflation on the real value of the NMW

The Panel is proposing an NMW of R3,500pm that will take full effect only in 2019 because enforcement is delayed until that date. This means that the incomes of some workers who currently earn less than R3,500pm will rise above that level by 2019 irrespective of whether the NMW is implemented. If that is so, then the Panel is overstating the number of potential beneficiaries.

The maximum possible number of beneficiaries of a higher minimum wage is less than the 6.2 million estimated by the Panel. This is because it includes an unknown number of people who work in the informal sector, in which a statutory NMW is irrelevant, and a further unspecified number of people who earn less than R3,500pm because they only work part-time. In addition, because the R3,500pm will not be enforced until 2019/20 by which point inflation will have reduced its real value, the correct point of comparison is with the number of people currently earning about R3,000pm in 2016

This reduces the number of potential beneficiaries by a significant, though unknown, margin even before two further critical factors are considered: the number of exclusions contemplated in the proposal(see Question 6) and the likely disemployment effects (i.e. job-losses) and the likely job losses that the NMW is likely to cause (see Question 8 and 9).

The Panel offers two separate justifications for setting the NMW at R3,500pm. The first relates to the impact of the NMW on poverty, the second to its affordability and supposedly benign impact on employment (see Question 8).

The Panel argues that an NMW that is too low to raise the working poor out of poverty would be problematic. It then estimates the amount of income needed to raise a household out of poverty in the poorest and second poorest income quintiles using a per capita poverty line of R779pm and the average number of people in each household. For the poorest 20% of households, household income of R4,100pm is needed; for the second poorest 20% (in which households are smaller), the figure is R3,200pm.

The Panel’s logic here needs to be questioned. It recognises that government provides both cash income and free services to poor households, but does not provide a framework for thinking about the extent to which this might impact on households’ needs for wage income. More importantly, the Panel does not ask whether poverty might be more effectively addressed through additional social welfare rather than an NMW.

Furthermore, by implicitly linking the level of the NMW to the income needed by households to escape poverty, and on this basis recommending an NMW of R3,500pm, the Panel appears to be contemplating a situation in which the typical poor household has only one member in employment. If the goal is to use the NMW as a basis for ensuring that household income is above the poverty line, it is important to be explicit about what assumptions are being made concerning how many people in each household will be employed.

According to the Panel’s data, this figure is currently about 0.6 for the two lowest income quintiles (implying that there is barely one employed person in every two households among the SA’s poorest 40%). This is the critical fact about the depth of SA’s crisis of unemployment, which every important policy document has highlighted. It appears, however, that the Panel’s proposal is premised on its never improving. This is a critical assumption that needs to be debated much more widely and rigorously. It is also linked to the critical question of whether an NMW of R3,500pm will impact on employment levels(see Question 8), The answer to this question depends, however, on the extent to which the Panel’s proposed NMW departs from existing wage norms.

The impact of an NMW on both households and firms depends largely on how significantly it changes the existing structure of wages in the economy: the higher it is, the greater its impact on poverty; the more out of line it is with current wages, the greater the risk that employers will not be able to adjust to it without contracting their workforce. In this regard, the Panel offers some evidence that is intended to suggest that the proposed R3,500pm is affordable but this is not entirely convincing.

By the Panel’s own calculations, nearly 50% of employed people currently earn less than R3,500pm with the figure rising to over 85% in both agriculture and domestic labour (see Question 3). These numbers may be somewhat exaggerated for reasons explained earlier (see Question 4), Even so, they represent very large proportions of workers in these industries, making it hard to see how a substantial upward adjustment in wages will not induce considerable disruption.

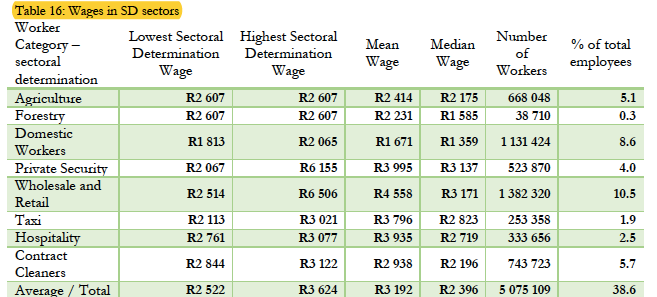

In addition, the Panel reproduces a table setting out minimum wages for 2014/15 as provided for through sectoral determinations by the Minister of Labour. This demonstrates that many sectoral minimum wages are much lower than R3,500pm. In many cases, this is true also of median wages and even of mean wages.

- DPRU (2016),

As is evident, from the above table, there are eight industries in which minimum wages for some categories of worker are between R1,813 (domestic workers) and R2,844 (contract cleaners). In none of these industries is the median wage higher than R3,171 (wholesale and retail trade), a figure that is nearly 10% less than the Panel’s proposed minimum wage. In the case of domestic work, the mean wage is less than half the proposed minimum. Some of this can be explained by the presence in the workforce of part-time workers (whose monthly wages may be close to or greater than R20ph), but the key take-away is that a very significant proportion of the workforce currently earns significantly less than the proposed NMW.

In these circumstances, to assume than an NMW of R3,500pm will be affordable and will, therefore, have a limited impact on employment, is to make a number of vital (if implicit) assumptions: (i) there are excess profits in these sectors or that firms will cut wages of highly paid staff to offset the impact of higher wages at the bottom, (ii) there are no possibilities for mechanisation in the industry, (iii) the firm’s owners cannot close shop to begin working in another industry or to relocate to another country. It is only under these conditions that firms would be able and willing to absorb the impact of higher minimum wages without reducing employment.

Proving the affordability of the proposed NMW in the face of the fact that firms pay much less than R3,500pm would appear, in other words, to demand significant evidence. The Panel’s approach, however, is to argue that an NMW of R3,500 is affordable because the ratio between it and median wages in the economy, at 0.78, is not out of line with the approaches taken in other developing countries. They argue that the NMW will be affordable because it is about 78% of the value of median wages in the economy as a whole, a figure that is not out of line with other developing countries’ minimum wages. Critically, however, when the Panel embarked on this exercise, it first excluded agriculture and domestic labour – precisely those industries in which wages are lowest – from its calculation of the median wage.

The exclusion of low-wage workers from the calculation of the NMW’s affordability is problematic. The median wage rises if you exclude large numbers of low-wage workers, making the proposed NMW appear more affordable than it would otherwise. It is not at all clear why policy-makers should use any conclusion drawn from this skewed method. Attempting to rectify this, the Panel proposes some exclusions/exemptions from the NMW, including (for a short time) farm and domestic workers.

At the core of the Panel’s approach to the NMW is the conviction that its coverage must be as broad as possible. At the same time, the Panel recognises that there is a range of sectors in which immediate implementation of an NMW significantly higher than existing wages (see Question 6) will create disruptions and lead to unemployment. In some (but not all) of these cases, it proposes exemptions, exceptions and delayed implementation. Its reasoning in these cases is instructive.

Agriculture and domestic work

The Panel’s wage data show over 90% of SA’s 1.1 million domestic workers and 85% of 560,000 agricultural workers earn less than R3,500pm. As a result, it acknowledges that there is considerable risk of job losses in these sectors if an NMW is set at that level. For this reason the Panel recommends, without substantial justification, that the minimum wage in agriculture be set at 90% of the NMW, while in domestic service it should be at 75%.

There is a degree of ambiguity in the Panel’s recommendations about the phasing out of these sub-minimum wages. On the one hand, it seems to insist that no exceptions of this kind should be contemplated after 2019 and that these differentials should be eliminated by then; on the other, it says that no adjustments should be made to the tiers until after careful study of the effect of these wages on employment levels. The Panel, in other words, seems to be saying that an NMW should be universal unless it has negative effects on employment in these sectors. Why this should be the case in agriculture and domestic work but not in other sectors is left unexplained. It is hard not to conclude that the Panel is seeking to protect itself from two contrasting objections: (i) that it is not really recommending a universal NMW and, (ii) that it is indifferent to job losses that may result from its proposals. As in other areas (see Question 8), the Panel appears to be ducking its responsibility for making the trade-offs between higher wages and fewer job opportunities more explicit.

EPWP and care workers

Another group of vulnerable workers identified by the Panel is made up of those who earn low wages, but whose principal source of direct or indirect employment income is government. They include the large numbers of people employed by the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) and the employees of subsidised early childhood development (ECD) centres. There are no estimates in the Panel’s report on the number of EPWP workers at any given time, but because of the way these figures are compiled, it is likely that all EPWP and low-wage care workers are included in the 1.2 million community, social and personal services (CSP) workers who earn less than R3,500pmand who account for 37% of all workers in the sector.

The Panel’s ambivalence about what to do with these workers is evident. It states that it would prefer an NMW of universal application, but recognises that unless government allocates significantly more money to fund activities like the EPWP and to increase subsidies to ECD centres, the imposition of a high minimum wage will reduce employment and in doing so reduce the quantity or quality of services provided. It notes, for example, that the norms and standards governing ECD centres require that the ratio of teachers to children be no more than 1:19, but that a salary of R3,500pm, which is nearly twice what some teachers in this sector earn, will make the achievement of this impossible unless government’s subsidy is raised considerably.

The Panel’s response to this dilemma will not convince anyone who is aware of the constraints on the national budget:

“The ECD example is illustrative of a large and complex sector. These are essential public services which, in most developed countries and in many developing countries, are provided by government. In the South African setting, NGOs and NPOs provide these services on an agency basis on behalf of Government. The Panel is very concerned about the impact of a national minimum wage at a level of R3,500 on this sector. In essence, Government needs to ensure that this sector is adequately funded in line with its constitutional and legal obligations.”

It is clear from the above that the Panel recognises that there are sectors in which there is a strong probability that employers’ response to the implementation of an NMW at R3,500pm will involve a reduction in the number of people whom they employ. As we will see, the Panel does not accept that this response will be generalised across the economy (see Questions 8 and 9), although the basis for any distinction between the effects in these sectors and those in others is not obvious. Indeed, to the extent that distinctions are drawn, they are not convincing.

The most important question to be asked about the proposed NMW is its likely effects on employment. This is an issue of overwhelming importance for a country in which nearly 40% of adults are unemployed.

The Panel is aware of the risk, saying that:

“… an NMW set above affordability levels could have negative employment effects. This risk cannot be taken lightly …It is not necessarily true that the mere presence of an NMW will lead to reduced employment opportunities, but the potential of such an eventuality was one of the foremost considerations in the decision about both the level and implementation path for the NMW.”

The identification of this risk is the key reason for the proposed exemptions and delays that the Panel proposes for sectors in which wages for large numbers of workers are lower than the proposed NMW, as well as for sectors in which the state employs many low-wage workers (see Question 7).

The Panel acknowledges that it was presented with evidence from economists, both at UCT’s Development Policy Research Unit (DPRU, and from the National Treasury. This evidence projected that a high NMW such as R3,500pm would lead to significant loss of jobs.

The DPRU’s submission used a model which estimated between 200,000 and one million job losses with an NMW of R3,400pm in 2014 rands, depending on the specification of the model’s parameters, while the National Treasury’s model estimated over 700,000 job losses would follow the imposition of an NMW of R3,200 in 2014 rands.

The Panel also notes that the National Minimum Wage Research Initiative (NMWRI) based at Wits presented a report arguing that an NMW of R3,500pm would be pro-poor, would reduce wage inequality, and would boost growth. However it does not include whatever the NMWRI’s model reported for its impact on employment.

Confronted with these contrasting estimates, the Panel notes (i) that the future is unknowable but that, as a general rule, the results of such models depend on their assumptions; and (ii) that international evidence suggests that minimum wages do not have the dire effects often predicted (see Question 9).

A key criticism of the Panel’s work, made most forcefully by Prof David Kaplan, professor of business/government relations at UCT and former chief economist of the Department of Trade and Industry, is that, when confronted by these results, the Panel has simply waved its hands and insisted that “it was not the business of the panel to judge the accuracy of these models”.

Kaplan argues that, properly conceived, the Panel’s task was to make explicit the extent to which there is a trade-off between the level of the NMW and the disemployment effects of implementing it. This, he says, it did not do.

Kaplan points to a passage in which the Panel says that, in reaching the recommendation for an NMW of R3,500pm, it “carefully considered all of the evidence, debated the issues at length and reached what we believe to be a carefully considered level”. He argues that what the Panel has effectively done is substitute its own inscrutable “careful considerations” for what was actually needed: a reasoned, empirically-grounded discussion of the potential negative employment effects of its proposal to weigh against its potential benefits. In the absence of this, he notes, it is disingenuous to claim as the Panel does, that “The proposed number is intended to be just below the threshold where the effects on employment change from benign to negative.”

(1) How many job losses are needed before the impact of the NMW ceases to be “benign”, and who should decide this?

(2) How does the Panel know that R3,500 is “just below the threshold” where a benign effect becomes a malignant one, and with what confidence does it hold this knowledge?

The report, in Kaplan’s words, “does not pose, let alone provide answers, to any of these questions.”

The mere fact that the Panel provides no clear answer to the key question about the potential impact of the NMW on employment does not diminish its importance and policy-makers need to consider all the risks. If they did so, they would likely find that the Panel’s view that an NMW of R3,500pm will have “benign” effects on employment is not compelling. Indeed, some of the Panel’s arguments recognise this, whether implicitly or explicitly.

As pointed out in Question 7, the Panel recognises that far fewer care and EPWP workers will be employed if the implementation of the NMW is not matched by an increase in government funding of these programmes. Similarly, the Panel recognises that agricultural and domestic workers, the great majority of whom earn less than R3,500pm, are vulnerable to job losses. Beyond this, the Panel offers little explicit argument about whether similar constraints might affect other employers, but does suggest that one of the keys to making the NMW work is for firms to find ways to raise worker productivity.

The ambiguous merits of productivity gains

In a number of places in its report, the Panel emphasises that a potential beneficial effect of setting an NMW that is high relative to existing wages is that it will encourage firms to find ways to increase productivity. This is one of the reasons why it seems enamoured of the NMWRI’s projection that an NMW of R3,500pm could actually increase growth. In addition, the Panel’s report concludes with three short sections, each of which amounts to a call for policies that would promote productivity gains through (i) more effective “industrial and productivity-focused” policies; (ii) prioritising R&D expenditure; and (iii) increased spending on human, physical and digital capital and infrastructure.

The flip side of this explicit focus on the desirability of increased productivity is that the Panel also says that it was “particularly exercised by those low-skilled sectors where there is limited scope for labour productivity improvements to accommodate higher wages”. In this regard, it is clear that the Panel is worried that these sectors – agriculture, domestic work, and low-skill manufacturing – may find it harder to adapt to a higher wage environment. It notes, for example, that many low-skill, low-wage tradable industries such as labour-intensive clothing manufacture, cannot be easily mechanised. Given this, it worries that firms may struggle to adapt to a higher wage environment. It is largely for this reason that sub-minima are introduced for agriculture and domestic work and that an implementation period of two years is proposed, so that the effects of the NMW on firms can be assessed. All of this implies that the Panel understands and accepts that it is possible that some firms are not going to be able to adjust to higher wages by improving productivity, and that they may have to downsize or close as a result. The Panel appears willing to accept this risk. The key debate for policy makers in Nedlac and elected representatives in Parliament is whether this is a risk worth running in a country with one of the world’s highest unemployment rates.

There is, in any event, a more fundamental problem with the Panel’s preference for firms adapting to an NMW by raising productivity, which is, by definition, a process whereby firms find ways to produce the same amount of output using less labour.. In other words, the Panel’s “solution” to the challenges firms will face in paying higher wages, is that they should find ways to produce their goods and services with fewer workers. This, of course, would make economic activity in SA even less labour-intensive, and leave the country less able to create jobs for its millions of unemployed people. It also runs counter to the general thrust of the National Development Plan.

It is important to recognise that the full impact on employment of an NMW that is considerably higher than existing wages will not be felt immediately. Nor will it be fully apparent in the course of the two years in which the Panel proposes firms find ways to adapt without fear of sanctions for failing to comply with the NMW.

Some firms may downsize dramatically or close immediately in the face of a high NMW. Others (probably the majority) will adapt more slowly by changing their production techniques so as to rely less and less on unskilled workers who earn the minimum wage. Initially, this may be by laying off only the least productive of their existing low-wage staff or failing to replace them when they leave. Over time, however, firms may mechanise their process or find different – more skill- and capital-intensive – activities. Some may shift production to other countries such as Lesotho and Swaziland, as some firms in the clothing sector have already done.

In other words, the impact of a high NMW will be to greatly reinforce all the existing dynamics in the economy that are pushing firms to rely less and less on unskilled labour. Nor is the effect limited to tradable sectors, as the Panel seems sometimes to suggest. Partly in response to the likelihood of rising minimum wages, for example, McDonald’s in the US has begun experimenting with outlets in which customers place their orders using touch-screen technology. This would allow the firm to make do with fewer workers and, for that reason, raise the average productivity of those who remain.

The Panel clearly favours higher productivity activities and appears to view the long-term reduction of low-productivity activities as being in line with the core aims of the proposals, rather than as a potential weakness. Whether or not one agrees with the Panel’s assessment on the desirability of moving up the productivity ladder, this implies that job destruction will occur in both the short and medium terms. Immediately, because not all firms will be able to adapt to higher wages and some will have to downsize or close; and over time, as they adapt their production techniques to raise worker productivity.

The Panel therefore seems to think that job destruction is bound to occur. Why, then, does it insist that there is evidence that high minimum wages do not reduce employment?

One of the recurring themes of the Panel’s report is the insistence that the international evidence does not support alarmist assessments of the impact of minimum wages on employment. It states, for example, that “The international literature shows that the aggregate effect of the implementation of the NMW on employment is marginally negative or neutral, often statistically undetectable, and sometimes positive”, before adding that “[a] review of global studies has shown that minimum wage-employment elasticities are relatively benign based on international evidence.” This conclusion is tempered, however, by an important qualification: those ‘benign results’ will not hold for any level of a minimum wage. And therein lies the rub. The Panel knows that the proposal it is making for SA in 2017 marks a very substantial departure from existing wages at the bottom of the labour market. This is apparent from the fact that, by its own estimates, 47% of SA’s workers earn less than the proposed figure (see Questions 3), and from the fact that its proposed NMW is significantly higher than the minimum, median and even average wages in a number of sectors (see Question 6).

It is worth noting recent comments by Princeton’s Alan Krueger, perhaps the leading figure in the study of the effects of minimum wages, and the co-author of the most important studies upon which policy-makers rely when arguing that minimum wages do not reduce employment. Writing in 2016 about the proposal to raise the federally mandated minimum wage in the United States from around $7 an hour to $15, a proposal that would affect the wages of over 50% of workers in some states, he noted that such a move would take policy-makers into “uncharted waters” and concludes that it was a risk that was simply not worth taking because of the high likelihood of unintended and adverse effects.

In most countries, a minimum wage is changed only when the labour market is relatively tight, which limits the likelihood of job losses. One of the key reasons why the international evidence does not show high levels of job destruction as a result of changes to the minimum wage is that those changes have been designed to avoid job destruction by focusing on a relatively small group of low-income workers. The failure to detect any significant impact on employment, in other words, is the result of the nature of the labour markets in which such policies have been tried and of the care taken by policy-makers to avoid job losses. To use these studies to justify an NMW in which these conditions do not obtain is misleading and horribly risky.

Obviously, the impact of a modest adjustment to a minimum wage that affects only a relatively small number of people is likely to be much less significant than the impact of a large increase that affects a much broader swathe of workers. An undertaking of this scale is much less common in international experience, and may never have happened on the scale proposed by the Panel in any country anywhere in the world. It has certainly not been tried in a country in which nearly 40% of adults are unemployed. For that reason, any reliance on the ambiguous, mostly benign results from other contexts is enormously risky. It is a risk, however, about which the Panel is either unaware or indifferent.

Although it mentions them in passing, the Panel does not endorse (or repudiate) the claim made by the NMWRI to the effect that an NMW of R3,500pm might actually raise economic growth. The NMWRI obtains this effect, the Panel reports, because its model “allows for positive benefits from the implementation of a minimum wage through productivity increases in workers, and positive externalities from the greater income share of labour.” The equations and mechanics of of NMWRI’s model are reflected in the Panel’s report, so it is not clear how this result is achieved. It is likely to rely on a presumed increase in aggregate demand attendant on higher incomes for the working poor, though this, of course, would depend on increased household incomes not being offset by similar losses elsewhere in the system through job destruction or lower incomes for non-poor consumers.

Although the report records no submissions on the potential of an NMW to impact negatively on GDP, it is hard to see how the estimates of large-scale job destruction presented by the DPRU and the National Treasury (see Question 8) would not also imply a negative effect on aggregate demand and economic output. This will not be proportionate to the decline in employment, however, since it is low-wage, low-productivity workers whose jobs will be destroyed.

Nevertheless, given the scale of job losses, there is likely to be some significant disruption in economic activity in several sectors, with an implied risk of lower (and perhaps negative) growth. Reduced economic growth would have adverse effects of its own: if, for example, GDP declined by 2% relative to its pre-NMW trajectory, the ratio of SA’s debt to GDP would rise, with implications for the cost of borrowing, interest rates, etc. In addition, tax revenues would fall, making it harder for government to sustain both its pro-poor spending and its investment in human and physical capital, and necessitating adjustments to fiscal policy and spending plans. These effects would not necessarily apply, of course, if all firms were able to adjust to the NMW by raising productivity, but, as discussed in Question 9, even the Panel appears to accept that some firms will not be able to do this.

Intriguingly, the Panel presents no argument or evidence about an issue that one might have expected to appear in a report proposing a big wage increase to a large proportion of all workers: whether or not this will simply result in higher inflation. This is a striking omission given the concerns that are often expressed by economists and policy-makers about the lack of competition in the economy and the resulting pricing power that many firms and industries enjoy.

Is it more likely that retailers, hairdressers and taxi bosses, for example, will absorb the full effect of an increase in wage costs, or that they will pass at least some of these on to consumers? Producers of tradeable goods might be less able to do this unless they can secure increased protection from foreign competition, but even without this, there will be many firms and industries with some capacity to pass on higher wage costs. Many services, for example, face no meaningful international competition.

It is not possible to state definitively what precise effect an NMW of R3,500pm in 2018/19 will have on the key metrics of poverty and inequality. On the one hand, some workers and their families will benefit, notably those who are currently earning less than R3,500pm, whose employers comply with the law, and who do not lose their jobs. There may even be some workers who do even better than that: if a firm currently employs five workers, four of whom are paid R2,000pm and one of whom is paid R3,000pm because she has more responsibility or experience, the employer may have to raise the fifth employee’s wages to more than R3,500pm if she is to maintain the differential needed to reflect her greater responsibilities.

So some workers will definitely benefit from the proposed NMW. If these were the only consequences, the result would be a reduction in poverty and some compression of the distribution of wages, leading to lower inequality relative to pre-existing patterns and trends. This report has argued that these are very unlikely to be the only effects of a high NMW, whose fallout will include some job destruction, some job opportunities lost (i.e. never created), as well as a likely reduction in GDP and an increase in price levels. While precise estimates cannot be derived for these effects, in all likelihood their combined impact on poverty and inequality will certainly dilute and possibly overwhelm whatever positive effects the NMW has on these.

The NMW and job destruction

It is worth emphasising that, while the Panel reports receiving a submission in which the effects of the NMW on employment are benign, it also received submissions from economists at two long-established and well-respected sources of credible data, UCT’s DPRU and the National Treasury. These models predict that between 200,000 and one million jobs will be lost. (see Question 8). Nonetheless the Panel insists that models aren’t always to be trusted and that the international evidence suggests that the direst predictions about the effects of minimum wages are seldom fulfilled. However, there is plenty of evidence in the Panel’s report to suggest that they themselves think it is more than plausible that some job destruction will occur (see Questions 7 and 9).

It seems clear, in other words, that there is every chance of job destruction as a result of the NMW, that the Panel actually recognises this, and that it has reconciled itself to this outcome.

What the Panel does not appear to have taken into account, however, is that, in addition to the potential of some job destruction in the short-term, it is inevitable that higher wages will lead both existing firms and those that are yet to be established, to opt for economic activities that require less unskilled labour and, in some cases, to relocate their operations to other countries. This trend, which is a key reason for SA’s already very high levels of unemployment, will mean that future economic growth will absorb fewer and fewer unskilled workers, leading to even higher levels of structural unemployment in the long term.

The NMW and GDP

To the extent that a high NMW reduces employment, it is very likely to reduce aggregate demand and GDP. This, however, depends to some extent on the number of people whose wages increase as a result of the NMW, and whether that effect will offset the reduction in aggregate demand attendant on job destruction. As pointed out in Question 11, any reduction in GDP (or in the rate of growth) could likely mean higher interest rates and lower tax revenues. Both effects will make it harder for government to afford the redistributive programmes it already undertakes or to afford the many investments that are needed to support faster economic growth. Lower GDP and a diminished capacity for the state to effect redistribution, will mean more poverty.

The NMW and inflation

The potential of the NMW to lead to higher prices was not discussed in the Panel’s report, though there is every reason to think that some higher costs will be passed on to consumers (see Question 11). To the extent that a broad increase in wages generates inflation, it will have even more ambiguous effects on poverty. For workers whose wages rise, it is likely that the increase in prices will not offset the full benefit of increased income. But for those who are not members of the working poor – whether this is because they are not poor or because they have no work – the resulting inflation will reduce purchasing power and lower living standards. The possibility that some of the increase in wages will be paid for by consumers, many of whom will have not derived any benefit from the NMW, appears not to have exercised the Panel.

The NMW’s effects on poverty and inequality

Despite the impossibility of offering precise estimates, it seems clear that the balance of risk is that a high NMW would increase rather than diminish SA’s already exceptionally high levels of poverty and inequality. This will be the result of a number of developments: job destruction in the short term and reduced labour absorption over the medium and long terms; likely reductions in GDP growth leading to lower per capita GDP; less redistribution through the fiscus; and higher inflation.

A sober examination of the proposed high NMW reveals unacceptably high levels of risk and a very high chance of exacerbating poverty, inequality and unemployment, while also slowing economic growth. Should a country in SA’s position with one of the highest unemployment levels in the world – close to 40% of the workforce – play Russian Roulette with the livelihoods of tens or hundreds of thousands of people?

Related posts

-

Fixing our SOEs for a growing economy and a brighter futureOctober 21st, 2024

-

How can we make SOE’s work?October 18th, 2024