Jobs crisis needs new approach

As the jobs summit nears, dire employment figures underline the urgent need to revisit SA’s core policies.

SA’s unemployment crisis is the deepest in the world and the forthcoming jobs summit needs to grapple with the scale and horrendous consequences of mass unemployment. This is something that President Cyril Ramaphosa acknowledged earlier this year when he said that the summit “will need to take extraordinary measures to create jobs on a scale that we have never before seen in this country”.

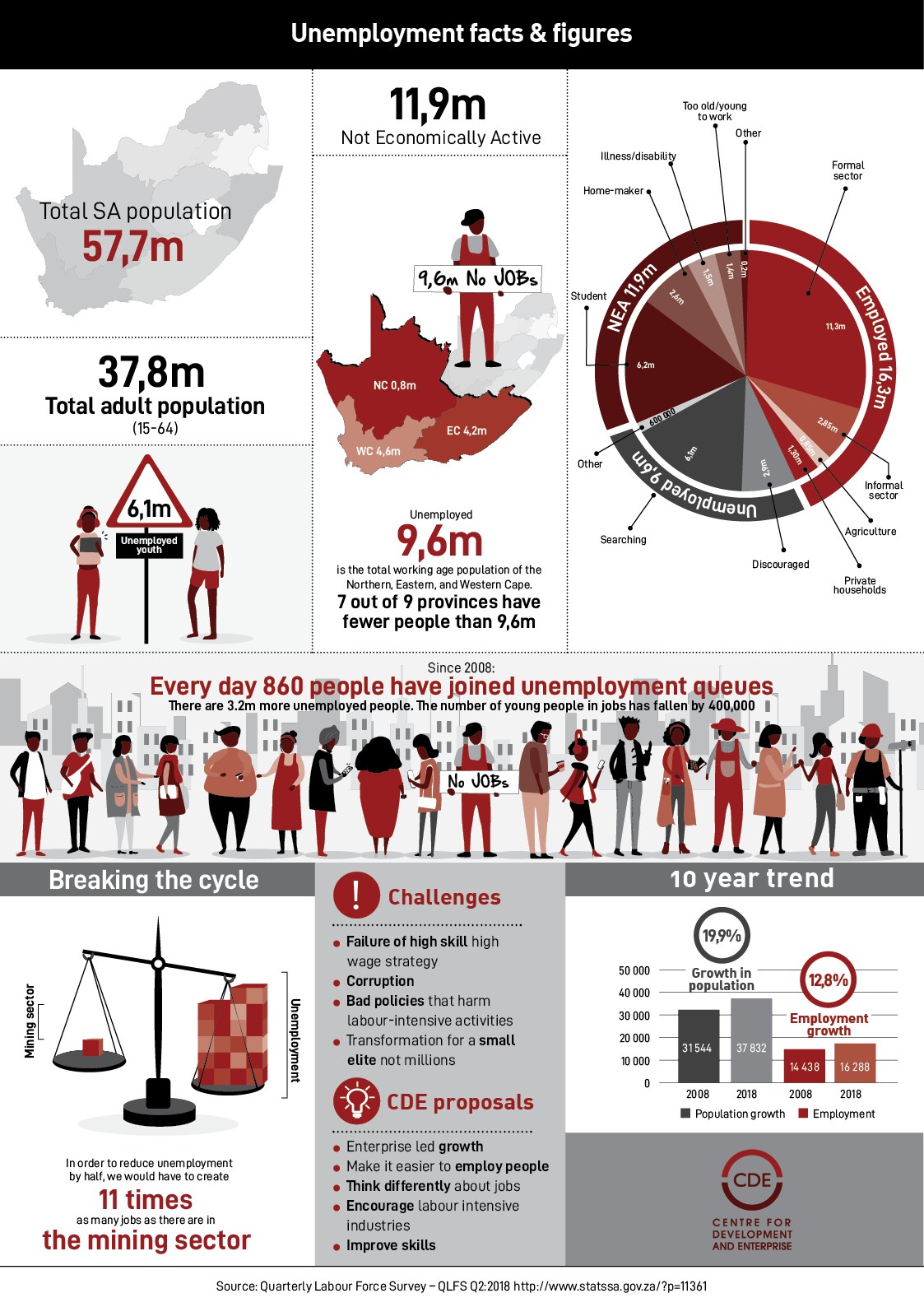

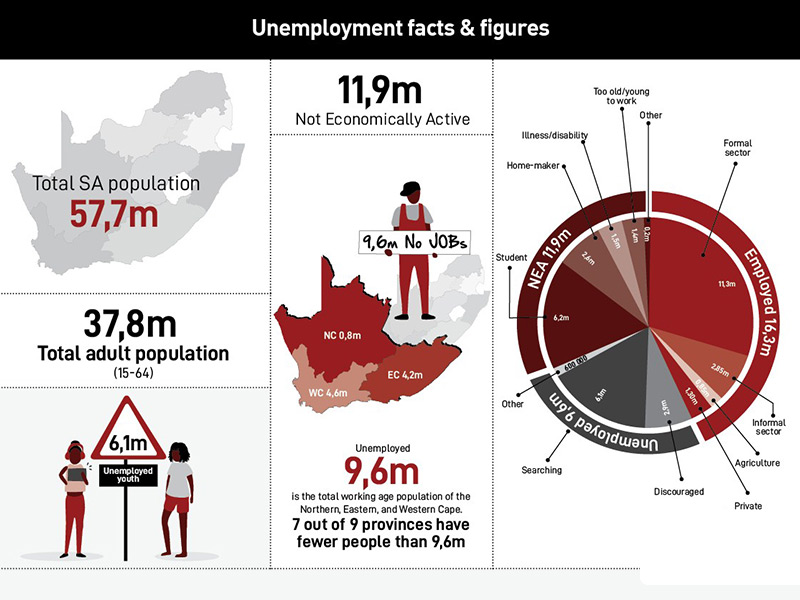

He’s right about the need for extraordinary measures because the scale of the unemployment crisis is enormous. There are 37.8 million working age adults in SA today. Of these, 11.9 million people mostly students and school pupils are not economically active. Of the remaining 25.9 million, 9.6 million 37% cannot find work. That’s almost two adults in every five.

Put another way, only about 43% of SA’s adults work. In most countries, the figure is 60% or more.

And matters have grown worse over time: between 2008 and 2018, the number of working age adults increased by 6.3 million but of these only 1.9 million 30% found work, while 3.2 million over 50% joined the unemployment queues. That’s an increase of almost 900 unemployed people in the population every single day for more than 10 years.

Matters are even worse for young people, for whom the unemployment rate is 50%, and there are 400,000 fewer people in employment in 2018 than there were in 2008 despite the number of young people having increased by 2 million in that period.

The 9.6 million unemployed mean that there are more people looking for work in SA than there are people living in seven out of nine provinces, and, if you wanted to reduce the unemployed by half, you would need to create industries that employ 11 times more people than are currently working in the entire mining sector.

The implications of all of this are devastating. SA’s mass unemployment is the key cause of poverty and inequality, contributing immeasurably to social dysfunction and political instability. Worst of all, unemployment is a terrible waste of human potential and an assault on human dignity.

And yet there is nothing inevitable about SA’s scandalously high unemployment rate.

A key reason for the unemployment crisis is that policymakers have been driven by a set of ideas about employment and the labour market that are unsuited to the challenges we face.

In essence, the government has chosen an approach to employment that insists workers must receive relatively high minimum wages and considerable legal protection from dismissal. The policy thrust and intention is that jobs that do not meet these requirements are not the kinds of jobs employers should be allowed to offer.

Effectively, government policy argues that no wage is better than a low wage. SA’s labour market policy has prevented the creation of the kinds of jobs that are the first point of entry for unskilled workers into modernising economies, whether in Europe and the US or the industrialising countries of Asia.

The ideological aversion to these jobs is disastrous. It is also in direct contravention of the advice of many international experts, who, time and again, have said SA must create jobs for the many unskilled workers we actually have and not the skilled workforce we wish we had.

Compared with the alternatives most unemployed people have rural or urban misery and hopelessness, dependence long into adulthood on parents and grandparents, a life of struggle in the informal sector, dominance of many women by fathers, brothers, husbands , working in a factory for low wages would be attractive to many hundreds of thousands of people. And these basic jobs are not an end point, they can lead as they have in almost every other country to better jobs and other opportunities in time.

For those who have one, there are big advantages in having a high paying, well protected job. But the cost of setting high minimum wages and standards that all employers must meet is that too few jobs are created.

One implication of recognising these challenges is that it shows up the inadequacy of job creation projects that address only a small number of beneficiaries. Far too much energy by the government, business and civil society goes into projects that help move some people into the employment queue, and not enough into policy reforms that have to take place.

We all need to recognise that commercially viable firms are by far the most effective, sustainable and economically efficient job creation projects, and we should do everything in our power to help remove constraints on firms. The most critical of these are the rules that raise the costs of employment and those that make employers reluctant to employ more unskilled and inexperienced young people.

Too many of SA’s industrial sectors are marked by high levels of concentration, with a small number of dominant companies. However, this is less the result of anticompetitive practices by businesses though, of course, this does happen , and more the consequence of policies that raise the cost of doing business to the point where only capital intensive firms can thrive.

Real reform would include exempting small and newly created firms from many existing regulations, and making SA a competitive place for light manufacturing to attract the many jobs leaving China.

Creating an environment in which companies are able and encouraged to create large numbers of low skill jobs is the single most important step SA could take to make its growth path more inclusive.

Unless core policies are revisited and soon, yet another generation will grow up in a world of mass unemployment and hopelessness.

Bernstein is the executive director of the Centre for Development and Enterprise.